|

SECTION I

THE YUMA DISTRICT: AN INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the Yuma District

The Southern Pacific Lines, comprised of the rails of

the Southern Pacific Transportation and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad Companies,

join 15 states with over 15,000 route-miles of railroad, the largest

percentage of which lies in the Golden State of California. The Los Angeles

and West Colton Divisions contain 10 percent or 1500 miles of those

routes, spanning from the Arizona border

to the central California

coast.

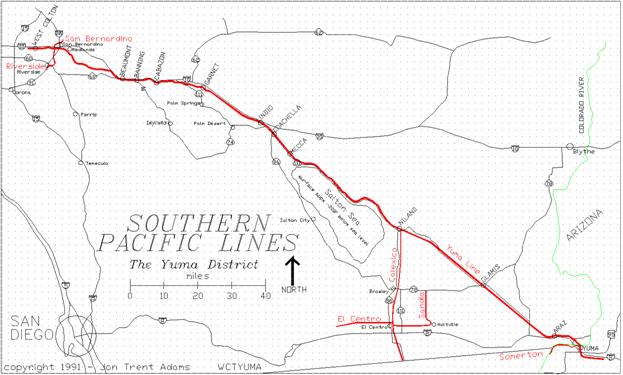

The Yuma District is one of five in the West Colton

Division; it extends from West Colton,

California to Yuma,

Arizona. The Yuma Line is the major artery under

the control of the District, with the San Bernardino

and Riverside branches serving the Inland

Empire area while the Calexico, Sandia, El Centro

and Yuma Valley Railroad branches support the transportation needs of

the Imperial and Yuma Valleys

in Arizona and southeastern California.

In the past, the Yuma District has been called the Yuma

Subdivision; the SP seems to change the appellation back and forth over

time.

The Reason for a Guidebook

What is the purpose of this guidebook? It's to assist the SP rail enthusiast,

the railroad modeler, perhaps even the occasional SP employee to have

a better sense of feel for the Yuma District and the country through

which the railroad passes. It's

for the armchair railfan, for the folks who would rather not fight the

traffic, the desert, the heat.

It's for the railroaders who for whatever reason can't get to

the Yuma District, whether because of distance, money, health, or bad

tires.

This guidebook attempts to provide an general overview

of the railroad as it existed in 1990. I tried to pay attention to detail so that,

as I said before, if you're not able to get out and about the Yuma District,

that by reading this you'll still get a good feel for the railroad and

its physical plant.

Guidebook Format

The guidelines that are set forth in the following paragraphs

are exactly that; these are the rules of observation and reporting that

I attempt to follow while researching the

railroad. They

will also help to explain features of the book and the methods for measurement

and recording.

What To Include in a Guidebook

A difficult problem was what to make note of and what

to ignore. I hope that I

have recalled all the pertinent details and left out most of the chaff. In areas where there is a dense population

of railroad features (signals, switches, bridges, grade crossings) this

isn't a problem. There is

always something to write about and there are plenty of landmarks and

points of interest for the reader.

But in the stretches of spare country, like between GLAMIS (MP698.1)

and CACTUS (MP712.3), there are few landmarks to go by and so I will

pay a bit more attention to minor drainages, power lines and dirt roads.

Data Collection Techniques

Like many of you, I have spent weekends cruising the

Tehachapi Loop, checking out the Lone Pine Branch (Trona Line), waiting

atop the Pepper Street Bridge at the east end of the Departure Yard

at West Colton, watching the action or the lack thereof.

I noticed that many others seemed to do the same thing, and that

everyone had their own secrets to successful railfanning.

I found no source of information that really described

the railroad at the detail that I desired, especially out in the forbidding

reaches of the Yuma Line. So

I began to write down everything that I saw or heard, whether from railfans

or railroaders. I used a

microcassette recorder to capture on tape many bits of information that

were too fleeting to stop the car and write down.

In all, compilation of this Guide has cost at least

several hundred hours of time in the field, a few dollars in repairs

to my car, and probably a failed relationship or two in my personal

life.

Explanation Of Descriptions

Being of moderately well-ordered mind, it seems apparent

that a sensible method of constructing a Guide is to write one that

uses the nearly ubiquitous Milepost as the index. So this Guide starts at the lowest Milepost

on a route, and proceeds upward.

By definition, this is always eastbound, although it's sometimes

less than apparent that the rails are going anywhere near eastbound.

Location names are printed in CAPITAL letters for three

reasons. The first reason

is that it may be a station or siding and so is called out in the Southern

Pacific Western Region Timetable dated October 1987. Second, it may also signify a name of a

specific place referred to by either train crews or by the dispatcher. An example of the first instance is "the

west switch of North GARNET Siding"; Garnet siding is described

in the Timetable. Of course,

the third reason is that the reader can see it that much more easily

during a quick scan of the manual.

A fine example of the second occurrence is the BLYTHE

CROSSING (MP612.9); this is actually where Dillon Road crosses the railroad tracks

at the southeast end of Indio. Although not called out in the Timetable,

SP crews near the Dillon Road grade crossing will sometimes call out

this name where asked for a location by other crews working in the same

area. Why? Because along Highway 86, parallel to the

railroad, there is a highway sign indicating to automobile drivers and

also visible to the train crews, that the town of Blythe is "thataway"

down Dillon Road.

Almost all switches not directly coupled into the main

track will have a number stenciled on their target. This number refers to the spur that the

switch controls and not to the switch itself. Examples of this are the interchange tracks

at Niland: The same numbers are on the switch targets at either end

of the track (tracks 0592, 0593 or 0594).

So technically the switch labeled 0594 at around MP666.9 would

be described as "the switch (or turnout) at the west end of 594". But in some cases the spur is single-ended,

and therefore there is only one switch target with that number, as exists

at the equipment spur 1145 near the west end of Glamis siding. The point is that although the number is

specific only to the spur track I will use that number to refer to either

the switch or the spur; the text description will (hopefully) clarify

the reference.

Routes

The Yuma District consists of the Yuma Line and six

branch lines that act as feeders.

The Yuma Line is the primary portion of track in the District,

and certainly the most important freight route and through route for

the traffic coming from the west coast and headed to the southeast and

east; depending on season, the southern route can be safer, faster and

more reliable than the central route through Nevada,

Utah and into Colorado.

The guidebook stresses operations on the Yuma Line,

with auxiliary chapters on the various branch lines within the District.

Mileposts

The guidebook is organized by milepost: the guide begins

with the lowest milepost number and, in the case of the SP, travels

eastbound. I have made numerous

trips along the right-of-ways in both directions, and I debated at some

length as to how I could construct a book that could be read either

east to west or west to east. I

looked at other types of guides that I have seen in the past; I could

see no simple way to present a bi-directional trip log.

If you intend to travel the route east to west, then you'll have

to read backwards, just like me.

Mileposts along the SP are almost always marked with

a milepost sign. Sometimes

a trackside signal line pole doubles as the post, but often there is

a special pole devoted to milepost duty, sitting all alone, perhaps

even on the opposite side of the tracks from the signal line poles. In a few instances, the milepost sign (the

number board) is missing, but on these occasions you can usually recognize

the post since the lower half of the post itself is painted white. If the whole post is missing, you'll have

to rely upon your odometer or upon the "count the poles" method.

The signal line poles along the right-of-way support

power, control and signal wires that carry the commands that the dispatcher

issues to operate the railroad.

There are, on average, about thirty-three poles per mile. Depending on the soil type, weather conditions

and such there may be more or less; the minimum number I have counted

between mileposts is twenty-five and the maximum nearly forty.

While wandering around along the right-of-way, I will

often use these poles to estimate my position with respect to the mileposts.

For instance, if the number of poles per mile has been averaging

30, the distance covered by three poles is about 0.1 mile.

This comes in handy when you find that your odometer is inaccurate

or there are few culverts or bridges with stenciled markings indicating

their locations.

I could have used pole count for the distances as described

in this book: for instance, the bridge at MP673.7 I could have described

as MP673+27, where 27 is the number of poles east of the 673 milepost

marker. Although it might

have been of some added ease for a few people, I realized that the majority

would prefer the locations given in actual miles, so that most could

consult maps without necessarily having to have been there.

However, some of the distances I measured in making up this guide

are based upon pole count.

Measurement Accuracy

The accuracy of my measurements is about 0.1 mile; therefore

I do not display more precision than that. I always round down to the previous 0.1

mile. The bridge that crosses

the American Girl Wash has the location 715.78 stenciled upon the abutment;

I will include this bridge in the list of items for the milepost 715.7.

Often there are multiple items of interest in a given

tenth mile; generally the guide book will always list the features in

order of location. However,

the most predominate railroad features in that tenth mile will always

get top billing over any other observations, with the following text

clarifying the order of appearance.

An example is the following listing from Milepost 576.5:

576.5 MONS

Crossovers

East Switch Mons

Siding

West Switch Fingal Siding

EB/WB Absolute

Signal Towers

Colorado River Aqueduct Crossing

Fingal Siding Length 11373'

The most important structure is the Mons Crossover itself,

followed closely by the fact that this location is the east end of the

Mons Siding and the west end of the Fingal Siding; there are signal

bridges at either end of the crossover.

Lastly, the Colorado River Aqueduct that supplies the majority

of water to Southern California passes under the tracks just a few dozen

feet west of the west end of the Crossover.

Also note that there are a few irregularities concerning

the mileposts: the tracks cross Mammoth Wash on a 200' bridge with the

marked location of 679.98; however, the 680 milepost is immediately

west of the bridge. Therefore

sometimes the mile markers aren't exactly where they should be. Often it will seem that the distance between

mileposts is not exactly 1.00 miles. It rarely is.

Mysterious Alphanumerics

OK. So you

read that MP552.7 is the site of the EL CASCO Station. Then immediately after that entry, the

mysterious "RIV9BB6" appears.

What's that, you ask?

I had to standardize on some set of maps for the reader

to begin with. The United

States Geological Survey topographical maps (topos) are a wonderful

trove of invaluable mapping information, but aren't generally much good

as day-to-day highway maps. Since

the Automobile Club of Southern California is not in the habit of distributing

their fine maps to the general public, the next best are the publications

of the Thomas Bros. Map Company and the DeLorme Company.

Both companies provide a set of mapbooks that cover

all of California

in varying levels of detail. "RIV"

refers to the Thomas

Bros. Riverside

County mapbook;

"9B" is the mapbook page, "B6" are the x-y coordinates

on that mapbook page. The

combination of the Thomas Bros. "Riverside & San Bernardino

Counties Street Guide and Directory" can get you in reasonable

detail all the way to about Ferrum Station at MP639.

From there, the "Southern California Atlas and Gazetteer"

published by DeLorme provides reduced resolution and detail all the

way to the Colorado River and Yuma

and to well beyond MP740.

Errors, Corrections and Plain Untruths

Most all of the field observations taken for this Guidebook

were made between March 1989 and May 1991. I have strived to report accurately all

the information in this Guide and have attempted to keep the errors

to a minimum since there is little advantage to me to fabricate untruths. I have no affiliation with the Southern

Pacific, except as an interested observer and have no secret hot line

to the people in the know. In

fact, as was mentioned in the book The Southern Pacific, 1901 - 1985

and from personal communications with SP employees, much of the history

of the company is lost to the company.

What remains rests outside the company and in the minds of the

employees and retirees of the railroad.

Since the Southern Pacific is a living, dynamic entity,

there will be regular changes and modifications to its equipment and

physical plant, and what is in evidence one day may be nothing more

than a bit of subroadbed or a few scattered ties a month later. I therefore cannot guarantee anything more

than that I have made an honest attempt at reporting.

I welcome any information from readers that helps to

clear misunderstandings that I might have inadvertently caused. I also hope that those with additional

information about the railroad's history in this region will come forth

so that it may be included in any future editions (Hope Springs Eternal)

of this Guide. In fact,

I hope that there will be subsequent editions that cover other portions

of the Southern Pacific Lines, the Santa

Fe and other interesting railroads.

Reference Materials Used for this Guide

There is obviously no one book that has provided me

with the information that this book contains. (If there was, I would have bought it instead

of writing this). Of course

much of what is detailed here is through field work: personal reconnaissance,

talking with railroad employees, camping out along the route and watching

the traffic. Books about

railroading, California history, general

history, geology and geography, and newspaper articles pulled off microfilm

from a storage vault provide more input and breadth. The last and equally important are the

maps: old maps from a variety of sources printed over the last hundred

and fifty years, United States Geological Survey (USGS) Topographic

(Topo) maps, Defense Mapping Agency Maps, maps published by the Automobile

Club of Southern California, Thomas Bros. maps, freebie maps given out

by developers and museums, etc.

All maps that I had available to me have provided some input,

directly or indirectly, to the formation of this Guide.

The following is a partial list indicating the major

references used. The list

is not exhaustive, and I'm sure that there are many references that

I never saw that might provide me with a clearer picture.

Publications

"Western Region Timetable 2", Southern

Pacific Transportation Company, October 25, 1987

"Western Region Timetable 3", Southern

Pacific Transportation Company, October 29, 1989

"All About Signals", John Armstrong,

Kalmbach Publishing Co., 1957

"Trackwork Handbook", Paul Mallery,

Boynton and Assoc., 1977

"The History of The Southern Pacific",

Bill Yeane, Bison Books, 1985

"The Southern Pacific, 1901 - 1985",

Don L. Hofsommer,

Texas A&M Press, 1986

"Southern Pacific Country", Donald

Sims, Trans-Anglo Books, 1987

"Santa

Fe' Route To the Pacific.", Philip

C. Serpico, Omni Publications, 1988

"San Diego

and Arizona

Eastern", Robert Hanft, Trans-Anglo Books, 1984

"City-Makers", Remi Nadeau, Trans-Anglo

Books, 1955

Trains Magazine, CTC Board, Pacific Rail News, Various Issues

"Flimsies! The Newsmagazine of Western Railroading",

many issues

"The History of California", H. H. Bancroft, 1883,

Vol 1-7

"The Compendium of Signals", R. F.

Karl, The Builder's Compendium, Celeron,

NY, 1971

"The Southern California

Guide to Railroad Communications", James Ciardi, 1987

"Railroads of Arizona, Vol. 1", D. Myrick, Trans-Anglo, 1975

Unpublished List of Railroad Frequencies, Greg Ramsey

/ Brian Hunell, 1990

Mapbooks

and Maps

"Early California

Atlas - Southern Edition", R. N. Preston, Binford & Mort

Publishing, 1988

"San Bernardino & Riverside Counties Street

Guide & Directory", Thomas Bros. Maps, 1987

"California

- Road Atlas and Driver's Guide", Thomas Bros. Maps, 1988

"Southern California

Atlas and Gazetteer", DeLorme Publishing, 1986

"Los Angeles

and Vicinity", Automobile Club of Southern

California, May 1986

"Riverside

County", Automobile

Club of Southern California, March 1988

"San Bernardino

County", Automobile

Club of Southern California, June 1988

"Imperial

County", Automobile

Club of Southern California, June 1988

"Salton Sea", Kym's Guide, Triumph

Press, Los Angeles

1986

United States Geological Survey, 7-1/2 and 15 minute

maps

SECTION II

A POCKETBOOK HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY OF THE

YUMA DISTRICT

Introduction

The Southern Pacific Transportation Company (SP) spans

15 states with 17,000 route-miles of track - a western transportation

colossus. Since its earliest

beginnings in 1850 as the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railroad

serving southeast Texas,

the SP has formed an irreplaceable and historic link in the chain that

has given the West its strength.

The Southern Pacific In Southern

California: The Sunset Route

The history of the SP in California

begins in 1865 with the incorporation of the Southern Pacific Railroad,

its mission to unite the cities of San Francisco

and San Diego, meeting the Texas

and Pacific at San Diego,

to complete a second transcontinental railroad. A second railroad spanning the continent

came about as a result of this, but history would see that the Texas and Pacific was never

involved. This railroad

was to be the creation of the Southern Pacific, through its lessees,

all the way to New Orleans.

By 1874, the SP, which had known for some time the economic

importance of building a second, southern route across the country,

began to actually undertake the task.

This route would take the railroad south through California's

San Joaquin Valley,

up over the rugged Tehachapi Mountains, across the Mojave Desert and

down through Cajon

Pass. From San Bernardino, the rails would turn

east and forge across the Coachella and Imperial Valleys, cross the

Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona, and continue eastward through Tucson

to El Paso, Texas. The stretch

across Texas to Houston and New Orleans would be under the banner of the Galveston, Harrisburg and

San Antonio (GH&SA) and the Texas

and New Orleans

(T&NO) railroads.

Politics in Southern California put a detour in this

most direct route; soon by congressional order the SP would be required

to abandon its route over the Cajon

Pass and instead drop into Los Angeles

via Soledad Pass, entering the Los Angeles

Basin at San Fernando. The citizens of Los Angeles had no desire to be on a hinterland

branch line of such an important railroad and by this Congressional

action they were able to coerce the railroad.

The year 1875 saw the Southern Pacific building down

the San Joaquin Valley

toward the Tehachapis; at the same time, an unconnected piece of SP

track was built in the Los Angeles area

from San Fernando to Spadra, near Pomona.

It would not be until 1876 that these two pieces of railroad

would connect at Lang, near the bottom of Soledad

Canyon, northeast of San Fernando.

Now that SP had grudgingly completed its involuntary

patronage of Los Angeles,

it turned its sights east again.

Beginning at the Spadra terminus, gangs laid track eastward toward

San Bernardino in 1876.

Negotiations with the city of San Bernardino

failed to produce any sort of monetary or real concessions for the railroad;

therefore, SP decided to avoid San Bernardino and created the new town of Colton, named after David

Colton of the Southern Pacific Company.

By fall of 1876 the railroad had made it up through

San Timoteo Canyon, south of Redlands,

and had begun the descent into the Salton Sink. Track building across the Coachella Valley

and the northeastern edge of the Imperial Valley

continued throughout the end of 1876 and into 1877.

The remaining miles across the southeastern tip of California were covered

during the summer of 1877. Soon

the railroad had arrived at the west bank of the Colorado River, immediately

across from the military outpost of Fort

Yuma, across the river in the Arizona Territory.

The Colorado River

was not the only barrier to further eastward progress. The Southern Pacific did not yet have congressional

authorization to proceed east into the Arizona Territory

and so the governor of the Territory forbade SP from bridging the river.

One story of the conquering of Yuma, told by Bill Yenne in his The History

of the Southern Pacific, involves the liberal use of whiskey. The SP threw a grand celebration under

a pretense; all the soldiers from Fort

Yuma were invited

to the bash. The soldiers

proceeded to drink heartily for some five days.

With the Fort out of commission, bridge-building and track-laying

crews spanned the river and laid track into Yuma.

By the time the soldiers had sobered up sufficiently,

the SP was established in Yuma. Although the governor attempted to force

them out, the local citizenry, enthusiastic with the coming of the railroad,

raised a vociferous protest which caused, in short order, the approval

of the SP action by the Territory and allowed for the continued eastward

progress of the railroad. The

Southern Pacific had won the war.

(However colorful this tale is, I suspect that reality

was a bit more monochrome, especially since there were only a few soldiers

stationed at Fort

Yuma; I repeat

it here because it's a cute story.)

By 1881 the railhead was at El Paso.

SP's corporate cousin, the GH&SA out of San

Antonio, was instructed to build west to meet with eastbound

Southern Pacific crews laying railroad out of El Paso.

In 1883 the rails met at the Pecos

River, nearly 300 miles east

of El Paso. The Sunset Route was complete - the second

transcontinental railroad finished.

GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY: The Setting for The Yuma Line

One hundred and ninety-five miles of some of the most

exceptional land on the planet separate West Colton,

California, from Yuma, Arizona. The whole country is shaped by planetary

geotectonic forces that manifest themselves as the San Andreas Fault

Zone, a thousand-mile-long crack in the Earth's crust separating the

North American and the Pacific crustal plates.

Los Angeles and the southern coast of California

are attached to the Pacific Plate while most of the rest of North

America rides upon the North American Plate.

The Pacific plate is inching its way north relative

to the North American Plate, and this movement over millions of years

has created the high mountains of the San Bernardino

and San Jacinto

Ranges, along with the deep, arid trough

of the Salton Sink. Few

other places on the planet have such differing environmental conditions

within the space of a few miles as southeastern California.

The Southern Pacific Railroad leaves West Colton, high

on the western bank of the Santa

Ana River;

the rails cross the river five miles east and one hundred twenty-five

feet lower in elevation. At

the river crossing, the railroad is approximately 950 feet above mean

sea level (AMSL). East from

the river crossing the route climbs through Loma Linda and into the

San Timoteo Canyon, the major drainage from the San Timoteo Badlands,

themselves a wrinkled artifact of the busy San

Andreas fault system.

This canyon provides the only reasonable access to the San Gorgonio

Pass, a 2600' Above Mean Sea Level (AMSL) saddle between the 10,804'

Mount San Jacinto and 11,503' San Gorgonio Peak, lying south and north

of the eastward-trending pass and a mere 21 miles apart.

The railroad passes through the town of Beaumont, at

the top of the pass, and drops into Banning, then Cabazon and finally

West Palm Springs before reaching the Coachella Valley floor at Garnet,

about seven miles north of Palm Springs.

The eastern descent from the pass follows closely the drainage

of the San Gorgonio and Whitewater rivers.

The Coachella and Imperial

Valleys define the bottom of

the Salton Sink, with the man-made Salton Sea

currently covering the deepest portion of the sink. The railroad continues southeast from Garnet,

easing down from about 680' AMSL to sea level at the outskirts of Indio, following a near

straight-line path first surveyed over a hundred years ago and now sheltered

from the wind and sand by towering groves of tamarisk trees.

Indio is about 15' below sea level; the rails continue southeast

through Coachella, then Thermal and Mecca,

before bending around the eastern flank of the Salton Sea, where the

railroad is fully 200 feet below sea level. The SP qualifies for the sole honor of

being the railroad built furthest below sea level - the next closest

are railroads (if any) built to waterfront on the Caspian Sea in central

Russia, at a depth

of 92' below sea level. But

at the onset, the SP rails sank even deeper.

The Salton Sea

The Salton Sink has suffered repeated bouts of natural

flooding from the Colorado River. Lake Cahuilla

is the name of the ancient, natural body of water that has occasionally

occupied the Sink; the highest recorded shoreline for this lake was

44 feet above sea level. This

is known because the lake rested at this level long enough for the wind-generated

waves to cut significant benches into the surrounding countryside at

the 44-foot level.

The Salton Sea is a modern analog of Lake Cahuilla

and an artifact of man's existence in southeastern California. In 1901, land speculators and a few major

property holders created the California Development Company, the goal

of which was to bring Colorado River water to the parched but fertile

soil of the Imperial Valley. An

experienced canal-builder and real estate speculator from Los Angeles joined the effort and designed and engineered

the Alamo Canal,

tapping the waters of the Colorado River and bringing them through the

Mexican desert into the Imperial Valley,

a distance of nearly seventy miles.

This proved to be a tremendous boon to the region; the

soil was extremely rich and the climate allowed year-round growing cycles.

The plentiful water from the Colorado

allowed the land, along with the developers' pocketbooks, to blossom. But all was not well. The speculators had dug the canal cheaply,

and had not concerned themselves with the vagaries of the river. Several times in the following few years

the headgates of the canal suffered minor damage due to flood flow on

the Colorado; in 1905 the river succeeded in breaching the inadequate

structure and quickly the rushing water carved a path nearly a half-mile

wide and carrying nearly the full flow of the Colorado.

The Salton Sea was reborn.

The railroad had originally gone south-southeast from

Mecca,

made the sweeping bend east and then angled back to the southeast near

the townsite of Salton. The

tracks continued down through the depths of the sink until well south

of current Bombay Beach;

here the line fell to nearly 270 feet below sea level. The rails turned southeast again and headed

straight toward Niland, back to its present-day course.

The task of the repair of the break and the plugging

of the flow would fall to the Southern Pacific. They would spend two years and over twenty

million dollars, and would have to move their right-of-way through the

sink several times in a constant retreat from the rising water level

in the Sea. In 1907 the flood was finally halted; the

Salton Sea stood at 210 feet below

sea level. Evaporation and

inflow from the farming operations in the valley have stabilized the

surface at about -228 feet.

There is apparently no evidence remaining of the original

route. The current route

follows the 200 foot contour line around the south side of the Bat Cave

Buttes, heading northeast before turning once again to the southeast

at Frink Siding.

The Imperial Valley

The Salton Sea rests at the north end of the Imperial

Valley, filling most of the valley floor remaining between the Santa Rosa Mountains

on the west and the Orocopia

Mountains on the

east.

Over the past few millenia, the Salton Sink has suffered

repeated flooding, making a vast inland sea that would slowly evaporate,

only to be repeated again. But

quite regularly this land would be well below the surface of this saline

lake.

The Bat Cave Buttes and the Salt Creek Wash between

Ferrum and Bertram sidings are eerie, incredible examples of what the

floor of the sea is like. Hiking

around there, the ground is smooth, eroded and clay-coated, with every

handful of dirt producing a dozen tiny shells of the various sea creatures

that lived in this lake.

From Wister, the railroad begins the climb out of the

bottom of the sink and passes through Niland, about 150 feet below sea

level. The tracks continue

the gentle climb up the bottom of this ancient lake toward the ancient

shoreline, just west of MP676.

Obvious signs of the approaching shoreline and beach happen at

about MP675.3 where the rails cut through a ridge; atop this ridge is

where waves broke on an ancient beach.

The land beyond the shoreline is the East Mesa; the railroad continues southeast along this plateau,

skirting the northern tip of the Sand Hills, themselves a result of

the strong easterly winds blowing the fine sand from the bottom of the

Sink. The rugged Chocolate Mountains

and the Cargo

Muchacho Mountains

define the eastern edge of the valley through which the tracks pass. The western side is bounded by the Sand

Hills.

South of Glamis the railroad continues onto the Pilot

Knob Mesa; in the far distance the spire of Pilot Knob itself is visible

and the tracks will aim at this mountain for the next twenty miles. All the drainages from the mountains along

the east carry stormwater into the natural sink of the Sand Hills in

the west; these flows can be heavy as is evidenced by the number and

size of the culverts passing under the roadbed.

The Yuma

Valley

Just past Dunes at MP723 the path bends east and begins

the descent toward the Colorado River; the rails pass across the south

shoulder of the broad alluvial fan emanating from the Cargo Muchacho

Mountains, using

cut and fill to cross the multiple south-trending gullies and washes. The final few miles to Araz switch are

followed by the double main track that snakes down the remainder of

the alluvial ridge, crossing the All-American

Canal and riding

out promptly onto the broad floodplain.

The tracks continue east on a high embankment across

the fertile, irrigated farmlands of Winterhaven; the Winterhaven crossover

rests upon this fill which can reach a height of some thirty feet.

The railroad originally crossed the Colorado River about

a half-mile west of the current steel bridge; the alignment took the

rails across the river and down the center of Madison Street in Yuma, Arizona. Today, evidence of this path has faded,

with a few sections of embankment on the California

side and a broad open swath running through the middle of Yuma's downtown district. In 1926 the modern steel bridge was opened

to traffic, anchored in the two hills that act as a gate for the Colorado River.

The Yuma railroad station

is situated about 0.5 miles south of the crossing at MP732.7 and is

the crew change point and is technically the meeting point for the Los

Angeles (now West Colton)

and Tucson Divisions. In

actuality, the West Colton Division maintains jurisdiction of the railroad

all the way to the division marker at MP738.8 as part of the Yuma District.

Sightseeing the Yuma District: Driving Out There

The railroad for most of its entire distance is bounded

either on the north or south by an access road. In general the placement of important equipment

like signal boxes and signals will be on the same side of the tracks

as the road. This way signalmen

and other maintenance-of-way folks needn't cross the tracks to get to

most of the equipment. This

road is usually the main route and sometimes the only way for rubber-tired

vehicles to have access to the rails. It can be rather rough, and very

tough on a vehicle.

There is no single proper vehicle for getting to 99%

of the locations addressed in this book.

The family sedan will work as well as a high-clearance four-wheel-drive

truck with big tires and little Chromium Cuties on the mudflaps. The patience, skill and plain daring of

the driver count for a lot.

Ground surfaces vary from paved road to gravel to loamy

soil to sand to rock flour to sheer, unadulterated glop. All but the last are approachable in the

family car (unless you or the family car has a death wish). The most important thing is to know how

to drive for the conditions and to be prepared for the consequences

when you make a mistake. And

this is not a primer on desert driving.

I tend to do most of my sightseeing alone; I have gotten

myself buried in the dust at old Tortuga Siding, had the battery die

at Iris, almost mired in the thick powder at Colorado, stuck in sand

drifts near Salvia; trapped in the mud near Brawley, and lost automotive

trim everywhere. If you

see bits of a 1981 tan diesel Rabbit, they're probably mine. But the point remains, I've never yet not

been able to dig myself out. It's

just a matter of preparation, perspiration, persistence and maybe a

little luck.

One of my mottoes is (or should be): "When in doubt,

walk it out". In other

words, if the road ahead looks chancy, get out and check it on foot. If confidence returns upon inspection,

you might want to go onward. But

remember, getting stuck without the proper supplies is crazy. And both my lawyers and I want you to remember

that I didn't tell you to do ANYTHING. In fact, that's why I wrote this book.

So all you'd have to do is sit in a cozy armchair at home and

read.

This railroad runs through one of the hottest, driest

and most desolate pieces of desert in the Outback. Bring water. I repeat: Bring WATER. During the warmer months bring LOTS of

water, which means at least a few gallons per person per day.

Carry a two-way Citizens' Band radio. Or if you're so inclined, get yourself

a Amateur Radio License. Or

carry a cellular telephone but remember, there's not much coverage in

the backcountry. Carry a jacket for the chilly nights and

a supply of food. Buy (and

read) a book on desert survival.

But don't go out unprepared.

It's not fun when the only alternative is a ten-mile stroll in

120 degree heat.

Weather

Be prepared for extremes. Mainly high temperatures, to be sure, though

winter evenings through the San Gorgonio Pass can drop into the teens;

the air temperature on summer days east of Niland can be greater than

120 degrees Fahrenheit; the ground temperatures are much higher. I know; I've measured it. Check with the National Weather Service

or other local weather information sources before heading out; heat,

cold or thunderstorms can be problematic at best or deadly at worst.

High winds and blowing sand can especially plague the

Coachella

Valley near the mouth of the San Gorgonio

Pass; this natural sandblast can etch your car's windshield. Of course,

the fashionable residents of Palm

Desert have had

to live with this reality for a long time.

So you won't be alone.

Watch out for the extremely infrequent but very dangerous

flash floods in desert canyons and washes.

One of my friends has a personal story that details the innocuous

peals of far-off thunder followed minutes later by a large rush of water

roaring down the canyon, scouring the wash and nearly flooding his car. In August 1989 a fair bit of tracks from

the east end of south Garnet down to about Date Palm Drive suffered substantial damage

due to flooding, this out in the near flats of the Valley floor. Pay attention to where the clouds are and

where your vehicle and you are not.

Don't camp in a wash while there is any chance of rain within

sight.

SECTION III

RAILROAD PHYSICAL PLANT AND OPERATIONS

Introduction

The SP is more than a bunch of MBAs, accountants and

130 years of history; there are dozens of trains active over the district

at any time, somewhere on those 1500 route-miles of track. The physical plant is its complex, expensive

and dynamic skeleton, consisting of all the hardware that makes the

trains run, including the trains themselves.

Trackage: The Mainline

Within the Yuma District, the Yuma Line is the "main"

line that carries through traffic in the district. Beginning at West Colton at the junction

of the Basin District's Colton and Alhambra

Lines, the Yuma Line extends nearly two hundred miles southeast to Yuma, Arizona,

handing off traffic there to the Gila Line of the Tucson Division.

Much of the traffic that uses the line is either originating

or completing its journey at Los Angeles,

and often at the ICTF complex in Wilmington,

between Long Beach

and San Pedro. The remainder is through-traffic, with trains running

to and from the Bay Area and Oregon

regularly rolling up and down the Yuma Line, carrying vast assortments

of products bound for the middle of the country.

Trackage: Branchlines

There are six active branchlines within the District.

Until October 1989, the San Bernardino and Riverside

Branches were part of the Yuma District; between them there is maybe

ten miles of track. In the

Imperial Valley, the Calexico Branch separates from the

Yuma Line at Niland, leading south to the Sandia and El Centro Branches,

a total of about seventy-five route-miles.

Finally, at Yuma

the Somerton Branch (Yuma Valley Railroad) peels off from the mainline,

providing yet another six route-miles of track. All the branch routes together constitute

less than half the length of the main line within the District.

Trackage: Yards

Although there are several places along the railroad

that qualify as railroad yards, West Colton Classification Yard is the

only facility of truly massive size; from one end to the other, West

Colton stretches over five miles in length, with fueling facilities,

a hump yard, service facilities and a major administration building.

Other, much smaller and less-busy yards include Indio, Niland and Yuma;

even these only see a few movements a day.

The interchange yard at Ferrum is currently used only for storage;

El Centro sees occasional

activity.

Trackage: Trackside Detectors

Trains are mechanical beasties, and pretty tremendous

mechanical beasties at that. There's

lots of stress and strain on the rolling stock, and that impacts the

trackwork, generally in an adverse manner. And sometimes the trackwork affects the

trains. Behold the trackside

detectors.

This is a generic class of devices that replace the

folks who, back in the days when salaries were lower, were paid to sit

and watch trains all day. By

doing so they could check for jammed brake shoes causing overheated

wheels, shifted loads that could endanger employees, bystanders or trackside

equipment, etc. Of course, most all those folks are long

gone now; but the need for early problem detection remains.

There are five types of detectors used within the Yuma

Sub; these are the Dragging Equipment Detector, the Hotbox Detector,

the High Water Detector, the Barricade Detector and the High/Wide Detector.

The Dragging Equipment Detector consists of a set of

vertical steel vanes on a rotatable shaft; this shaft lies across the

tracks, underneath the rails, and is connected to a mechanical rotary

switch in a box adjacent to the rails.

The vanes reach up just to the height of the railhead, waiting

for trains to pass over. If

there are loose couplings, hoses, understructure parts or even a derailed

car, this dragging material will strike the vertical vanes and rotate

the attached shaft, causing the rotary switch to close and setting of

the dragging equipment alarm.

The Hotbox Detector is a device that is sensitive to

the infra-red energy emitted by hot objects; as a railcar passes over

the detector, the hotbox detector "looks" at each wheel and

bearing set, checking the temperature of each and setting off an alarm

if the critical threshold is exceeded.

It consists of a pair of low, angular, cast boxes that are fastened

to the tie surfaces on the outside of the rails.

The High Water Detector is a vertical pipe with an internal

float; placed in a streambed or anywhere potentially destructive amounts

of water can accumulate, the detector is triggered when the water level

rises enough to cause the float to rise in the pipe, closing a switch

and activating an alarm.

The Barricade Detector is a general name for any detector

that trips when some large item goes somewhere that it shouldn't; either

a railroad car rolling off the end of a spur track and grounding itself,

perhaps tipping and fouling the main track, or maybe an automobile or

truck running off the highway and fouling the track.

In the first case it is a heavy metal bar that is broken when

a railroad car or engine rolls past; the latter case is generally a

cable strung along a row of posts, with one end of the cable attached

to a switch that closes when the cable is pulled or broken.

The last type is the High/Wide Detector; there is exactly

one in the Yuma District, an open, metal frame that bridges the mainline

tracks near Yuma. Attached to this frame are lamps that shine

a narrow beam of light into photocells also attached to the frame. Normally, a train rolling through this

framework will not cause any of the light beams to be broken; but, if

there is a shifted load, or an item that is stacked too high, the beams

will be blocked momentarily as the train passes through the detector,

setting off the alarm.

Trackside Equipment: Signals

Signals have help control train movement on the railroads

since the 1830s. They serve

the same purpose that the signals which control your nearby highway

intersection do: to orchestrate traffic movement for added safety and

efficiency.

There are many types of signal, but nowadays most all

employ electric lamps that display various colors, with each color having

a specific meaning. Gone

(at least in the Yuma)

are the old semaphore signals with a mechanical arm that was raised

or lowered to indicate traffic movements.

The standard signals used along the SP are called searchlight

signals, with a single lamp located in the center of a single, black

target at the top of a high staff.

Color changes on these signals are effected by the internal movement

of different color filters in front of the lamp.

Sometimes, added traffic control is required, with extra

searchlight signals added to the staff at lower points. Secondary signals are often on low staffs,

with reduced-size targets. Some

secondary signals are mounted directly on the ground; these are called

"dwarf" signals and are generally used where there is limited

mechanical clearance.

Signals can be mounted on towers or bridges; throughout

the Yuma Line, and especially between West Colton and Beaumont, there is a fine

display of nearly all the possible signal mounting variations.

Bridges and Culverts

There are only three ways (in our three-dimensional

world) to allow something to get from one side of the tracks to the

other; the first is a crossing at grade, where the cross traffic blocks

the main route. The second and third are variations of

one another: the overpass and the underpass.

When it comes to water, grade crossings aren't generally

a good idea (unless it's the locomotive washing facility). At least along the Yuma Line, all water

flow passes below grade, either by flowing through a culvert or by the

tracks being carried over the water on a bridge.

Culverts mentioned in this book are generally cast-concrete

pipes, either circular or rectangular in cross-section, and usually

(but not always) a maximum of a few feet across. There is an abundance of corrugated-steel

culvert pipes used also; these will either have a circular, oval or

arch cross-section. In almost

all cases, culverts are used where a fill was cheaper than a bridge

or other large structure; the culvert provides the passageway for runoff

to flow from one side of the fill to the other.

Bridges in the Yuma

are usually wood- or steel-pile trestle structures, constructed over

low depressions and streams where the volume of water flow is enough

to make the use of a culvert questionable.

Of course, if piles can be driven securely enough, a pile-trestle

bridge is a far less-expensive method of fording a gap than is a full-fledged

truss bridge.

As far as "real" bridges in the Yuma District,

there are two of note: the Pennsylvania Truss bridge over the Colorado

River at Yuma, and the box-trestle structure

over the Salt Creek Wash east of the Salton Sea. The rest of the span bridges are deck-

and through-plate girder ones, with single-span lengths up to a hundred

feet or more.

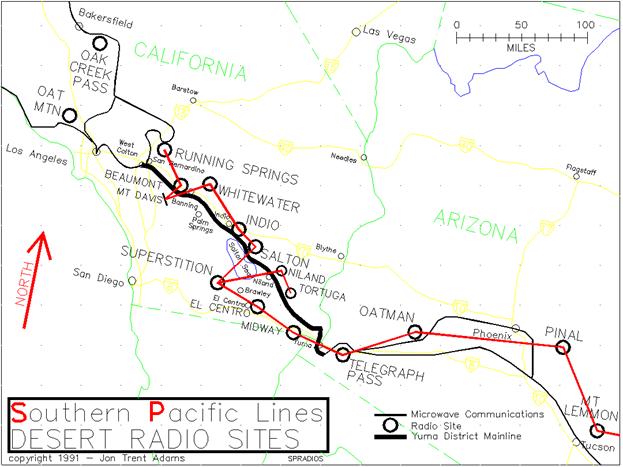

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS

The Southern Pacific, like all other modern railroads,

makes extensive use of the two-way radio for communications between

dispatcher and train.

All communications along the railroad are for the most

part carried on a private system of microwave-frequency radios located

at critical points. Each

of these sites usually employs one or more VHF radios to allow communications

with either train crews, Maintenance of Way employees or supervisory

personnel out driving about. The

microwave system is also tied to the standard telephone network.

In the Summer of 1989 SP moved all their dispatchers

to Roseville, California, as a economizing move. In the process the dispatchers were also

renamed. So now the old

East End dispatcher that used to control the Yuma District

is now called "WR (Western Region) 55", sometimes known as

the "White Rabbit"...

Radio Network

The frequencies used by the railroad in its daily operations

include the road channel, 161.550 MegaHertz (MHz), the PBX (Radiotelephone)

channel 2, 160.890MHz and the PBX channel 3, 160.950MHz. The SP police frequency is commonly 161.220MHz.

All these frequencies are in the region between the FM broadcast

stations (88-108MHz) and television channel 7 (approximately 175MHz).

Coverage of the west end of the Yuma District (West

Colton, San Bernardino, Riverside, the west side of Beaumont Hill to

about Banning) is provided by the Southern Pacific radio site at Running

Springs, about midway between Lake Arrowhead and Big Bear Lake high

in the San Bernardino Mountains.

Both the road channel radio and the channel 2 PBX radio are located

at this site.

East from about Banning all the way to approximately

Thermal radio coverage is supplied by the Southern Pacific radio site

at Whitewater Hill, a few miles north of the railroad at milepost 583. This radio site allows road channel coverage

and PBX channel 3 use.

From around Thermal or Mecca

all the way to perhaps Regina the railroad

communicates via the radios at the Southern Pacific's Superstition Mountain

site, located approximately 25 miles southwest of Niland. The road channel is available here and

so is the PBX channel 2.

Radio communication along the Pilot Knob Mesa between

Acolita and Dunes is supported by a radio site near Glamis; this site

employs an alternate road channel frequency, 160.845MHz, and may also

support PBX channel 3, the 160.950MHz frequency.

Further east, all the way to Yuma

and for at least seventy miles beyond the railroad uses the Southern

Pacific site at Telegraph Pass, immediately north of the Interstate 8 pass through

the Gila Mountains

just east of Yuma. The road channel and PBX channel 3 are

in usage here.

Up until January 1990, all of the PBX radios at each

site had voice identifiers that stated the site name and radio callsign

at the end of any transmission.

On PBX channel 2 (160.890MHz) at the Supersition Mountain Site,

a pleasant-voiced woman concluded all transmissions with "Southern

Pacific Superstition, KDB647, Out."

Likewise with all the other radio sites mentioned.

Then for a while the lady went away; currently her voice can

be heard on most of the radio sites outside of the Los

Angeles area. At Oat Mountain

and Running Springs the station identification is provided in twenty-word-per-minute

Morse code, which is not nearly as enjoyable to listen to.

But at least now the call letters of these sites are unambiguous.

The list of sites, frequencies and callsigns that are

bound to be heard at one time or another in the Yuma District are as

follows:

"Mount

Emma"

160.xxxMHz kkknnn

San Gabriel Mountains

10 Miles south of Palmdale, CA

"Running Springs"

160.890MHz KDB647

San Bernardino Mountains

18 miles northeast of West Colton, CA

"Whitewater"

160.950MHz KDB647

Whitewater Hill

10 miles northwest of Palm Springs, CA

"Superstition"

160.890MHz KDB647

Superstition Mountains

15 Miles west of Brawley, CA

"Telegraph

Pass"

160.950MHz KQL724

Gila Mountains

15 Miles east of Yuma, AZ

"Oak

Creek Pass"

160.950MHz WXB906

Tehachapi Mountains

15 Miles west of Mojave, CA

"Oat

Mountain"

160.950MHz WXB906

Santa Susanna

Mountains

8 Miles northwest of Van Nuys, CA

"Oatman" 160.890MHz KQL724

Gila Bend Mountains

25 Miles northwest of Gila Bend, AZ

(Note: The last three radio sites are separated by many

miles from the Yuma District. However,

depending on the time of day and your location, their signals can be

heard quite well sometimes and so are listed for your information.)

All along the route, occasional radio traffic will be

heard on the police frequency, 161.220MHz.

Sometimes this is by far the most interesting, with reports of

containers being burgled, trains being tampered with and vagrants (or

railfans) lurking in rail yards.

All in all, it pays to program your scanner to listen

to at least three of these frequencies: usually the most immediate traffic

will take place on the road channel, with extended conversations being

held on the local PBX channel, especially when a crew can't reach the

dispatcher on the road channel.

If you have a priority channel feature in your scanner, I suggest

that you set it so that radio traffic on the road channel has precedence

over all other traffic, so that you don't miss the immediate events

going on in your local vicinity. Listening to the police is also quite interesting

and sometimes even illuminating, especially if they're talking about

you!

Radio Monitoring and the Law

It is my opinion that you have an absolute right to

listen to, monitor, attempt to decode, decipher or whatever, any radio

signal that passes through your property or more personally, your body. And all radio signals do that. The Federal Communications Act of 1934

provides for this also; the major stipulation is that you do not use

any information so gleaned to commit crimes, nor are you allowed to

divulge to any other person the specific contents of any such communication.

However, please be aware that even if you follow all

these rules, some folks are naturally a little suspicious when they

come across you carrying scanners and loitering on private (railroad)

property. They might ask questions; you may

get hassled... But remember,

"Have Fun, 'cause it's only a Hobby".

TRAIN SYMBOLS

All of the trains that the SP runs are identifiable

either by their lead engine number or by a five or more character designator,

called a "symbol". In

general, most trains will use their engine numbers for identification. Occasionally, if the lead engine is defective

or there are other problems, another engine in the consist will become

the train number.

Sometimes a train is important enough to the overall

profitability of the railroad that it will be referred to by its "symbol",

rather than by just its lead engine number. Not only does the symbol indicate the origin

and destination of the train, but it also provides some idea of its

cargo and/or its priority.

An example of a "Symbol" train is as follows:

The EPOAA train is a train that begins at El Paso, Texas (trans-shipped

from the Union Pacific / Missouri Pacific there), consists almost totally

of tri-level automobile carriers filled with autos and trucks, and is

destined for Oakland, California.

In fact, this train will usually have a string of Union Pacific

locomotives on the head-end, with a single lead SP engine as pilot.

The following is a list of the abbreviations used for

symbol trains. This list

is by no means complete; I have only included names that you might tend

to hear along the Yuma Line.

AS - Alton & Southern

(East St. Louis,

MO)

AV - Avondale,

LA

AX - APL @ ITCF (Port of Los Angeles)

BA - Bay Area (San

Francisco, etc.)

BK - Bakersfield,

CA

CH - Chicago,

IL

CR - Conrail

DA - Dallas,

TX

EP - El Paso,

TX

ES - East Saint

Louis, MO

EU - Eugene,

OR

FR - Fresno,

CA

HO - Houston,

TX

LA - Los Angeles,

CA

LX - ICTF (Port

of Los Angeles)

MF - Memphis,

TN

NO - New Orleans,

LA

NX - NYK @ ITCF (Port of Los Angeles)

OA - Oakland,

CA

PB - Pine Bluff,

AR

PT - Portland,

OR

PX - Phoenix,

AZ

RV - Roseville,

CA

RX - Evergreen @ ITCF (Port of Los Angeles)

SJ - San Jose,

CA

SX - SeaLand @ ITCF (Port of Los Angeles)

TU - Tucson,

AZ

WC - West Colton,

CA

Symbol train names consist of five main characters;

the first four indicate the origin and destination of the cargo. The fifth character indicates the type

of train, but this isn't often apparent from the look of the train. These characters are:

A - Automobiles

F - Forwarder

K - Poisonous or Hazardous Chemicals

M - Manifest

T - Trailers and Containers

L - Local

X - Extra

There may be many others, but these are the most obvious

ones and the ones most commonly heard.

So when you hear the symbol NXMFT discussed on the radio,

that it is just leaving Indio after dropping

its helpers, you will now know that this is the train carrying the containers

from the NYK (Japan)

Shipping Company, offloaded from the ship and transferred to the railroad

at ITCF at the Port

of Los Angeles. The destination of this train is Memphis, Tennessee,

and it is technically a consist of trailers and/or containers. It will also be a very hot train and it

will be obviously moving eastbound at a good clip, if you can catch

it. Its top speed will most likely be about

what the rails can handle; since it does not carry high/wide cars or

cargo it will probably dust you if you try to chase it down State Route

111 along the eastern side of the Salton Sea. Remember, if you try to do this, the CHP

prowls that strip of highway and is always more than happy to oblige

you with a fat speeding ticket...

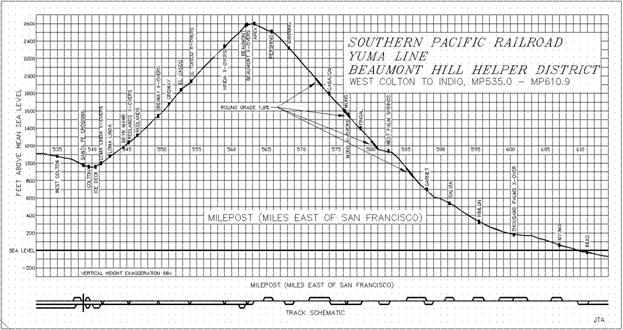

THE HELPER DISTRICT

SP is very fond of helper units on Beaumont Hill, between

Loma Linda Crossovers (MP541.3) and Indio (MP610.9). There are often many, many millions of

dollars of locomotives sitting at the PMT and Engine Spurs at Loma Linda,

waiting for the next eastbound to help push over the Hill.

Depending on the shortage of power for the District,

helpers can be switched in and out most everywhere along the Hill. Trains have been ordered to leave West

Colton and run as far east as they can before they stall; helpers rush

from Indio and other points to

eventually couple to such trains.

When a helper engineer gets the order from the dispatcher

to "run light", that means to finish whatever he's doing and

get his engine set going as soon as allowable to assist somewhere else

on the Hill.

Hanging out at most any siding on either end of the

Beaumont Hill will usually net some helper action during the course

of an active day; the best places to watch are Loma Linda, Thousand

Palms Crossover and Indio. But as I have said previously, units can

be found switching in and out at almost any other place in-between.

RAILROAD JARGON

I've considered trying to write a primer on the language

of railroading; this hasn't been simple since railroaders are humans,

just like you and I, and they tend to use different words occasionally

to describe the same thing or even make up new words and slang, conveying

the intended meaning through innuendo or familiarity. But here is a "minimal" listing

for those of you who don't listen to the scanner twenty-four hours a

day, or at least work for the railroad.

A few of the more interesting phrases sometimes heard are:

Stretch 'em out - Take out the slack in a train usually

by moving the locomotive forward a bit.

Bunch 'em up - Exactly the opposite. Remember that a 100-car train may have

a foot or two a slack between each car due to coupler and draft box

play; when the engineer applies the brakes the rear end of the train

doesn't get the message in a hurry due to all this slack.

When there were cabooses there was sometimes a cracked head or

two in the caboose when the slack caught up with the end of the train.

Bring it to a hook - Couple cars together.

Highball - OK to go. Throttle up. Pedal to the metal...

Come up against - 1) Tells the helper engineer in a

consist to push against the portion of the train between him and the

road engines at the front. 2)

Part of an order given by a dispatcher allowing a engineer to make a

movement against a stop signal and couple to a standing train, either

to lend helper service or to serve as road power.

That'll do - OK.

That's enough. Whoa,

horsey.

Scanner - Any one of the various equipment malfunction

detectors emplaced along the railroad.

There are so many esoteric and mysterious phrases used

by train crews that to attempt to list them all here would consume most

of the room reserved for real information.

The best way to learn the jargon is to tune in the radio for

many hours at a time and pay attention to the flow of traffic; then

when these mysterious phrases are voiced you might be able to piece

together the meaning. Or, you could ask someone who works for

the railroad... and maybe

get a completely different answer.

SECTION IV

RELATED SUBJECTS:

PRIVATE PROPERTY, RAILFANS AND TRESPASSING

The Southern Pacific Railroad is in the business of

providing a transportation service in order to make money; never forget

this. It does that by moving

material from Point A to Point C or perhaps Point Z. The railroad doesn't need you at Point

B or Point N fooling with the switchpoints or hanging off the signal

bridge, trying to get that one great picture of those eastbounds powering

up the grade (although it might be a tremendous picture; but I didn't

recommend it...).

Think of the railroad as a factory, a factory spanning

half the country. It has

a receiving dock that accepts the raw material and production lines

that process this material by moving it along great steel conveyor belts. The finished goods appear finally at the

shipping dock.

Now imagine you at your place of work having unauthorized

visitors sticking their hands and heads into your bending brake or file

cabinet or typing a few words on your computer. Although to you the railroad may present

unlimited photo opportunities or be the prototype for your model layout,

it is their company and their living.

Trespassing

I cannot condone trespassing; the legal difficulties

that could ensue would make me very unhappy. But as most everyone realizes, the railroads

are not generally fenced and there are few vicious guard dogs to protect

the rails from the curious. The

railroad employees (other than RR police) that I have met while poking

around have never yet asked me to leave the property; in fact, they

seem genuinely interested or at least amused that I as a railfan exist. After all, it's just a job to a lot of

them. They'd often rather

be somewhere else.

Railroad yards like West Colton

are another thing: I generally stay away from these places. The SP police are paid to look down on

folks climbing in-between classification tracks, poking their noses

into locomotives idling along the station or maintenance tracks, etc. And they are empowered by the State to

be real live Peace Officers, complete with the ability to arrest you

and carry a gun. If you

are intent on seeing facilities like this, ask permission first and

maybe they'll surprise you and say yes.

You have to realize, though, that they are liable for any injury

to you caused by your foolishness or carelessness and so they'd probably

rather not have you around.

A Few Trespassing Anecdotes

In one weekend while researching this Guide, I had two

incidents befall me regarding trespass.

(I can now look back upon them with some dark humor). The first was while driving along the paved

county road at MP579.4, stopping there a few minutes to jot some notes,

then turning off the pavement to follow the dirt path that parallels

the tracks to the east. Within

two hundred yards a CHP Mustang from out of nowhere had pulled me over

and, with hand resting on the butt of his pistol, the officer wanted

to know why I was out there and if I knew that I was trespassing on

Railroad Property. Of course, I was probably also trespassing

on Morongo Indian land, State and Federal land, etc., but I explained

that I was a railfan. Soon

he had my name and address and warned me that if he heard about any

trouble along the tracks I'd be the first suspect. And that was that. I sure hoped that there wasn't gonna be

any trouble around there for a day or two or three.

The second was the next day, under the Auto Center Drive

Overpass (MP611.4) at the Indio Yard. It was a hot (105 degree) day, twelve o'clock

high, and I parked under the bridge to stay cool, drink some water and

make some notes. This time

an Indio PD cruiser pulled up behind and I spent several tense minutes

explaining that I had nothing to do with the alleged in-progress vandalism

taking place on the train in front of me.

Finally the officer relaxed his grip on the holstered .357 when

he decided that I was too crazy to be lying.

He also discovered that he had grown up only three blocks from

where I live, so I suppose there was a certain kinship there.

Then he apologized and left me; his parting words were "Enjoy

the rest of your stay in Indio".

Railroad Property

You do not need souvenirs from Glamis siding. You don't need a Cabazon tieplate paperweight

or that bucket of spikes from Frink that weighs three hundred pounds

and makes your Ford Escort drag its rear bumper along the pavement. There is real scrap along the right-of-way,

but most of this you wouldn't want anyway: examples are the millions

(well, it seems like millions) of shoes on and in the ground at Garnet

Station or the Easter Baskets at Salt

Creek Bridge. The railroad probably wouldn't care too

much if you waltzed off with the shoes or the baskets. But then again, maybe they would.

Be wise. I

have listened on the radio to the railroad police arresting folks for

stealing piles of tieplates and spikes.

These items are worth good money, and the railroad can recycle

most all of the materials.

Federal, State and Local Government Property

There's a lot of this out there. Most of the desert still belongs to you

and me, with the Federal Government as caretaker (more or less; mainly

less). Some people look

on this as a bad thing; but for the most part, it's better than running

into barbed-wire fences every few miles and dealing with folks carrying

shotguns.

The railroad, once out of the San Gorgonio Pass, leaves

the confines of suburbia and sails through mainly uninhabited terrain.

Here the land surrounding the tracks is owned by a variety of

governmental agencies; for the most part, no one will bother you and

no one particularly cares. But so long as you are next to or near

the tracks, you are most likely on railroad land and that is private

property.

Indian Reservation

Land

Indian Reservations are private property; these folks

own that land and are free to make their own rules regarding trespass. They generally have their own police force,

and sometimes even their own jail.

But generally, as long as you aren't tearing up their land, or

stray too far from the beaten path, it's unlikely that you'll ever see

them. But again, it is private property, and

you are trespassing.

Trespassing On Anything Else

Although a great deal of the land along the right-of-way

belongs to the Federal, State or local Government, there is also a lot

of private land. The first

rule is: If you are on the wrong side of a "NO TRESPASSING"

sign you can get into trouble.

The second rule is: Even if there aren't any "NO TRESPASSING"

signs visible, if someone comes along and tells you that you're trespassing,

you might do well to pay heed.

They might be wrong, but unless you're in a position to prove

that to their satisfaction, you may want to move on.

Fruit orchards and farms line the tracks in places.

Farmers can get very upset if they find you filching their oranges

or whatever. Section 484 of the California Penal Code

makes it a FELONY to swipe fruit...

and there are signs all over that repeat that! When I stop at a store and buy fruit,

I even carry the receipts around with me until the fruit is gone and

I've buried the refuse. But

I'm paranoid. Being thrown

in jail for six months for having an illicit, 20-cent orange in the

back seat isn't worth it. (It's

a silly law, I agree; in fact, I'd say that it was cruel and unusual

punishment.)

Hanging out under that bridge or on that hill you may

be RAILFANNING, but other folks (the residents of wherever) might call

it LOITERING. The police

can then bring you TROUBLE.

Support Your Local Railroad

An important thing to remember is that you, as a rail

watcher, can provide an extra set of eyes and ears to the railroad. If you're out along SR111 by Ferrum Siding,

along the east shore of the Salton Sea,

and see some nasty-looking types vandalizing railroad property, report

it. Find a phone at your earliest convenience

and call the SP Police, the county Sheriff

or the Highway Patrol. They'll

appreciate it and maybe, just maybe, you'll engender a little respect.

In Parting

The Southern Pacific Transportation Company would like

railroading to remain a paying, profit-making business, with as few

liabilities as possible. If

you abide by the rules, you help out the SP, they can go about their

business of running more trains and in return you can enjoy the hobby

that much more.

Once again: Don't take railroad property, don't fool

with railroad equipment, don't get in the railroad's way, but always

have FUN. It's a hobby,

after all.

|